by Vic Olvir

From National Vanguard magazine No. 105, May-June, 1985

In the past quarter-century or so a rather peculiar fate has befallen American literature: the tradition of the American novel begun by such illustrious names as Hawthorne, Melville, Twain, and James, and carried on by such as Fitzgerald, Faulkner, Hemingway, and Wolfe, has now seemingly devolved upon writers whose names happen to be Bellow, Mailer, Malamud, Wouk, and Roth. Further, the critical establishment that nurtured and sustained the rise of the former group of writers has been transformed; it now consists more and more of Jewish critics reviewing Jewish writers in publications owned by Jews. This change in the racial composition of American literature’s ruling class has wrought a profound transformation in the moral and aesthetic quality of the literature itself; above all, it has imparted a new meaning — and a more intense truth — to anthropologist Hans F.K. Guenther’s observation, made over half a century ago: “[I]t is just those authors who are most praised today who promote … nothing less than the further decomposition of the spiritual and moral values of the Indo-European.”1

Historical Context

This ascendancy of Jewish literati, surprising in its completeness, is all the more astonishing when one considers the historical context.

First of all, many of the principal American novelists before 1945 were quite averse to Jews in their personal feelings, in their work, or both. Nathaniel Hawthorne, for example, after dining with a prominent English Jew, wrote of “the repugnance I have always felt towards his race.”2 As for Herman Melville, his attitude was “conventionally anti-Semitic.”3 Ernest Hemingway’s portrait of Robert Cohn in The Sun Also Rises speaks for itself. Thomas Wolfe, author of Look Homeward, Angel, was unfriendly to the Jews to such a marked degree that the well-known Jewish critic Leslie Fiedler, in his book Waiting for the End (Stein and Day, 1964), was “tempted” to say that Wolfe was not “German- American,” but “Nazi-American.” Even Jack Kerouac, the Beat Generation novelist of the 1950s, denounced the Jews and their influence.

It is clear that as recently as the Second World War organized Jewry had not consolidated the enormous power it now exercises over American values, at least with respect to literature. Jewry was unable to ban the works of a Hemingway or a Wolfe, or to bring those writers to heel. Prior to the war, in fact, there were few if any Jews who were even teaching American literature courses in the colleges, and for good reason. As Norman Podhoretz, the literary doyen and longtime editor of the Jewish intellectual monthly Commentary stated bitterly: “As late as 1937, it was thought that a Jew could teach philosophy or even Greek [in an American university] but that no one with such shallow roots in Anglo-Saxon culture could be entrusted with the job of introducing the young to its literary heritage.”4

Certainly, Jews in America were writing novels, in English, as far back as the late 19th century and through the early decades of the 20th (Abraham Cahan, Ludwig Lewisohn, Henry Roth, to name a few), but they made no significant impression on American readers, and not much on the critics, and none became “best sellers.” Jews at that time seemed unwilling even to support their own writers — despite claims made now that Jews constitute the largest part of the hardbound book-buying public. As late as 1944 Lionel Trilling, then a Jewish member of the literature faculty at Columbia University, declared in a Commentary symposium that “as the Jewish community now exists, it can give no sustenance to the American artist or intellectual who is born a Jew.”

Yet it happened that a mere two decades later “American” literature had assumed a Semitic countenance. What are the reasons for this?

Causes and Motives

The suddenness of the rise of the Jewish literary demigods and the obvious cooperation of forces that made this apotheosis possible justify likening the phenomenon to a putsch. Before examining the reasons — both the true reasons and the reasons offered by the Jews and their apologists — why this putsch succeeded, it is instructive to note that the Jews themselves were among the first to acknowledge the postwar Judaization of American letters.

The jacket blurb on Jewish writer Irving Malin’s Contemporary American-Jewish Literature (1973) crowed about the effects of the putsch: “The dynamic quality of American literature during the 1950s and 1960s unquestionably owes much to the brilliant contributions of Jewish writers.” In an earlier book, Breakthrough: A Treasury of Contemporary American Jewish Literature (1964), Malin was similarly unrestrained: “For the first time in history a large and impressively gifted group of serious American- Jewish writers has broken through the psychic barriers of the past to become an important, possibly a major reformative influence in American life and letters.”

Sol Liptzin, who taught comparative literature at the City College of New York before emigrating to the Promised Land in 1966, in his backward glance at the bad, old days when Semitophobic Americans dominated American culture, also let it be known that a new and glorious age had dawned at last: “Jewishness has become an important theme of American literature in the 1960s. The Jew has become a kind of culture hero among United States intellectuals and artists…. A new pattern was emerging in American fiction. Judaism was being painted in such attractive colors that a tradition of many centuries was being reversed.”5

Leslie Fiedler joined the chorus: “Certainly we live at a moment when, everywhere in the realm of prose, Jewish writers have discovered their Jewishness to be an eminently marketable commodity, their much vaunted alienation to be their passport into the heart of Gentile American culture…. Philo-Semitism is required — or perhaps, by now, only assumed — in the reigning literary and intellectual circles of America….”6

Why did this putsch succeed? An event so broad in scope and profound in effect will lend itself to different causal explanations, some more accurate and complete than others. White Americans must not lose sight of what is at stake — the very survival of their cultural values — and must be satisfied with nothing less than the whole, unvarnished (and un-Judaized) truth. Many distorted or half-true explanations have been offered by others.

One writer, for example, ascribed the Jews’ conquest of American fiction and the concomitant herdlike manner in which non-Jewish writers have fallen in step with the philo-Semitic dogma to guilt: “The Jewish writer was made the beneficiary of Hitler’s death camps. We Americans, spared the war’s worst horrors, had to know more about those piles of corpses, teeth, shoes, we saw in the newsreels. Whether out of guilt, morbid curiosity, or both, the Jew became important to us.”7 In itself this is unconvincing, although the weapon of guilt became significant when employed — over and over again — by the all-powerful machines of mass propaganda.

Irving Malin saw the matter from a rather nasty, messianic viewpoint. He opined that the poor, dependent Gentiles need a Jewish “transfusion” every now and then: “The Judaeo- Christian tradition needs, I fear, constant transfusions from a living Jewish body, not merely the initial impulse from a dead Savior and a Book.”8

Fiedler concurs with the message of Jews as deliverers: “The Jewish- American mind, conditioned by two thousand years of history, provides other Americans with ways of escaping the trap of vacillation between isolationism and expatriation, chauvinism and national self-hatred.”9

The reason most commonly advanced, however, for the Jewish dominance in American letters is that Jews, being aliens in America, represent the rootless, alienated, post- Second World War United States or, alternatively, the quintessential alienated artist. “From the larger American point of view,” writes Robert Alter in Commentary, “the general assent to the myth of the Jew reflects a decay of belief in the traditional American heroes — the eternal innocent, the tough guy, the man in quest of some romantic absolute — and a turning to the supposed aliens in our midst for an alternative image of the good American.”10

The victories, literary and otherwise, that Jews have won in America have indeed come about because they are aliens, outsiders with a strong tribal cohesiveness and an enormous will to power — but not because they are “alienated,” too sensitive by nature to feel at home in America’s anti-cultural, beehive society of “doers.” It is true that artists in America (and other cultures as well) are sometimes alienated, but that does not mean that they are completely cut off from the people and the culture of their origin, for that would be impossible. They are tied to that from which they are alienated; for their “apartness” to have significance there must be a specific and definable entity from which they are set apart. The artist can adulate or ridicule or hate that entity — the culture from which he grew — but he cannot be indifferent to it if his work is to exhibit any vitality. Even the most alienated artist will have others within his culture with whom he can speak, though they be but a tiny minority. Western artists who imagine that they are totally alienated from their society would understand the true meaning of that word if they were magically transported to an Incan city in the 15th century or to an Eastern European shtetl in the 18th century.

The truth is, the literary prominence that Jews have achieved in America has not been because they are an alienated minority, but rather the reverse: the Jewish literary putsch occurred concomitant with the assumption to power of the Jewish entity as a whole, with the shifting of the national consciousness from the country to the largely Semitized cities, above all to New York.11

People identify, perhaps subconsciously, with power; they want to immerse themselves in it. As weakness draws to strength, as the debilitated tend to seek a source of energy, as the feminine turns to the masculine, so do the people — including, above all, the intellectuals, the literati — turn toward the immense strength and prestige of Jewry, Jewish power, Jewish energy, while enjoying as a bonus the delusion that they are sharing somehow in the volcanic sufferings supposedly inflicted upon this martyred race.

The “Southern school” of novelists, whose popularity peaked in the ’30s and ’40s, represented the last redoubt of White American culture, one final backward glance before the country hemorrhaged and dropped confused and wounded into the arms of the Jewish entity. Power fascinates, and readers of novels, like others, sensed this new and strange power and desired to acquaint themselves with it, particularly since the controlled media were falling over themselves to trumpet the news that Melville and Hawthorne had at last found worthy heirs in the novelists ripened and tossed up from the American-Jewish ghettoes. It is not the Jews who have assimilated into American culture; quite the contrary. The American, above all the “cultured” American, has assimilated into Jewish culture. The consequence of this development has been disastrous: the evanescence of any literature that has any real meaning, that strikes any resounding chords in the hearts of American readers. It has left us with a cultural landscape as bleak as the most windswept of Middle Eastern deserts.

A good novelist tells an engaging story while distilling the essence of racial or national character. When both elements are melded in a seemingly effortless flow (as in Melville’s superb Moby Dick) the result is literature. Readers who share approximately the same heritage are engaged, because the characters act in ways more or less predictable from the readers’ own spiritual and psychological mainsprings. Even when the fictional creations behave in unpredictable ways, the surprises are always of a kind that compels the reader to nod in agreement. It may not be what the reader himself would have done, but he acknowledges the credibility of the unfolding plot.

What would not be credible, however, would be a character of the Western Culture acting totally out of his national and cultural context — say, for a hero from a Henry James novel or from Scott Fitzgerald or from Ernest Hemingway answering a question with his own barrage of rhetorical queries or suddenly behaving with the oiliness of a Jewish pushcart peddler. This would be merely bizarre and would destroy the reader’s identification with the character. Even those Gentile writers who ardently wish to imitate Jews can never really portray with complete verisimilitude the fawning flatterer whose tongue in a trice metamorphoses into a viper’s fang. This can be properly accomplished only by one steeped for millennia in a racial and cultural broth that makes of duplicity an admirable, natural, and instinctive virtue.12

The Jewish conquest of virtually all aspects of American life found its reflection in the arts. “The new Amalgam, the man, has been shaped in some unquantifiable measure by Jewish influences…. The ‘entertainment’ industry is very largely composed of secular Jews, many of whom have changed their names…. The political style of urban and suburban Americans has unquestionably been influenced by the Jewish minority….”13 This observation by Jewish scholar Allen Guttmann points up the fact that a subject people tends to imitate the style of the conquerors, and this is, unfortunately, all the more true among the readers of “serious” literature, who are weaker in will, more irresolute, more cowardly — in a word more “liberal” — than the unwashed, non-reading masses. Those who were at one time the receptors and the appreciators of the arts in America have, in effect, become ersatz Jews.14

Such a development did not, of course, occur without a strong push from the conquerors. No people can fight a bloody war against its own interests and expect to remain unscathed forever, and it was quite natural that Western values eroded rapidly in the United States after it took part in a “successful” war against Western Civilization. Jews, ever sensitive to shifting changes of climate, mobilized swiftly to take advantage, to thrust themselves forward as the referees and judges of artistic merit, of what, in the area of letters, deserved to be published and read and what did not.

This process was facilitated by the fact that New York City, which before the end of the first quarter of this century had become a de facto Jewish colony, had long been the most important publishing center in the country. Here the cultural putschists congregated, initially clustering around Commentary magazine and The New York Review of Books. This clique of Jewish intellectuals (with a few effete, philo-Semitic Gentiles thrown in) referred to themselves as “the family.”

|

| Norman Podhoretz |

According to “family” member Norman Podhoretz, they wanted to lay a serious claim to their identity as Americans and to their right to play a more than marginal role in the literary culture of the country. Both the claim and the right were a decade later to be taken so entirely for granted that one is in danger of forgetting how tenuous they seemed to all concerned even as late as the year 1953 — how widespread, still, and not least among Jews, was the association of Jewishness with vulgarity and lack of cultivation.”15

The family latched onto Saul Bellow and rapidly pushed him up the ladder of literary fame. “The family,” wrote Podhoretz, “had a genuine desire to see one of their own make it as an important American novelist….”

As with all usurpers, the family did meet some resistance. J. Donald Adams, of the now family- controlled New York Times Book Review, became “altogether explicit” and “moved dangerously close to [making] the same accusations against the Jewish influence in culture as those made by the Germans in the 1920’s and after.”16

But the complaints of a few refractory critics would not stay the hand of the Jews from their power-and-revenge imperative. So complete was the triumph that Podhoretz could openly boast of it: “American Jews had in past decades played a minor role on the literary scene (although a major one in the entertainment world), but now suddenly they were replacing the Southern writers as the leading school of novelists and so dominating the field of serious fiction that a patrician WASP like Gore Vidal could complain whimsically of discrimination: there was room, he said, in the lists of important American writers of his generation for only a single ‘O.K. goy.'”17

It is a curious thing indeed that Jews can boast of their cultural putsch and at the same time deny that they have any significant power. Jewish writer Richard Kostelanetz once spoke with amazing frankness (to a tiny literary-magazine audience) of the fraudulent tactics of the Jewish putschists, in their “double insistence of group innocence and importance. Perhaps nowhere else does it reflect its excesses more strongly than in the inflation, invariably by Jewish critics, of minor reputations…. Several magazines almost lie in wait to hail the arrival of another promising Jewish talent… One should not minimize the Jewish movement into communications and education….”18

The family was victorious everywhere, and so we have the decomposed state of “American” literature, circa 1985. Many of the major book-publishing houses in the United States are now directly controlled by Jews. Marguerite Pedersen, a small-press editor, believes the figure to be 50 per cent. “Of my own knowledge,” she writes, “I am aware that the big publishers accept virtually nothing for publication unless they know the writer. Most of the time they commission the book before it is written.”19 A large number of the flourishing small presses also have Jewish ownership, and most of those that do not are forever angling for money from the National Endowment for the Arts, a government agency that will hardly dole out its largesse to any publisher who deviates greatly from the official dogmas.

Most of the major publishers not directly controlled by Jews are owned by great corporate conglomerates stoutly committed to profit without problems, a problem being perceived as anything that goes counter to the official anti- White, pro-Semitic ideology. No major publisher today will issue books critical of powerful minorities or forthright about racial problems.

Nor may one look to the vanity houses for an escape from the iron dogma. Edward Uhlan, the master of Exposition Press, has for many years made a fine living devouring the savings of frustrated folks who yearn — and will pay — to see their manuscripts in book form. But don’t make the mistake of thinking Uhlan will print just anything for money: He will positively not touch “an evil book,” by which he means any book that is “bigoted” or “fascist.” He will print nothing, in other words, that would threaten or expose the incredible position of power his people enjoy in America the Beautiful.

Many publishers will not bother to read a manuscript unless it is submitted by an agent. Family members — an extended family now — dominate this turf also. Perhaps the top agent in New York is the Jew Scott Meredith (Norman Mailer, Spiro Agnew, and Carl Sagan are just a few of his many rich and famous clients): “There is almost nothing Meredith won’t market if there are profits in prospect,” states Newsweek. But even Meredith has his scruples — the usual ones: he won’t handle anything “racist or politically offensive.”20

All this comports rather curiously with a Jewish commentator’s remark that the demise of the “WASP cultural hegemony” is a “good thing, since variety is by and large a healthy condition in art, and since writers no longer have to feel constrained to betray some part of themselves by masquerading as members of the ‘dominant’ cultural group in the forms of literary expression they adopt.”21

This is the opposite of the truth, of course. Writers today must masquerade more than ever — as Jews.

The question recurs: What motivates these new conquerors? In this regard, one thing is clear: Not least among their motives is a self- conscious Jewish animus against the prevailing WASP cultural values. Consider the following remark from Podhoretz, one of the chief putsch- ists: “When I was in college, the term WASP had not yet come into currency — which is to say that the realization had not yet become widespread that white Americans of Anglo-Saxon Prostestant background are an ethnic group like any other, that their characteristic qualities are by no means self-evidently superior to those of the other groups, and that neither their earlier arrival nor their majority status entitles them to exclusive possession of the national identity.”22

Today, in fact, the Whites’ majority status does not entitle them to any possession of the national identity.

Winners and Losers

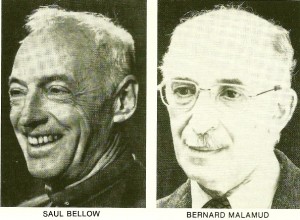

So it is: the putsch has prevailed, the WASP cultural hegemony is over, and the Jewish literati reign supreme. It is time to count the casualties and reckon up how much the putsch has cost White culture. The greatest harm, clearly, has been that done to the national identity. We will understand this better when we examine the qualities of its new, self-appointed custodians, as represented by some of their leading names: Saul Bellow, Bernard Mala- mud, Herman Wouk, Norman Mailer, and Philip Roth. We must also consider what effect this putsch has had on the English language — just what changes Yiddish-thinking minds have wrought on the native tongue of Shakespeare, Dr. Johnson, and H.L. Mencken.

To begin, let us take a look at the aforementioned purveyors of the fictive arts.

Bellow, best known perhaps for Herzog and Humboldt’s Gift, is one of the most egregiously pretentious phonies on the literary scene today. Malamud now writes mostly of Jewish issues, after an earlier effort at mythologizing — fake to its core — in The Natural. Wouk, the clumsiest of the group, puts out long, ponderous novels undoubtedly intended as soporifics for his New York brethren whose nerves are shredded by the spectre of street crime, or perhaps for the aunties in Brooklyn bored by the prospect of yet another night of Mah-Jongg. Mailer’s ambitious Jewish chutzpah has him grandly examining and explaining to us stupid goyim the significance of space exploration, American movie queens, mass murderers, etc. Roth is perhaps the easiest read for Gentiles, but only because the snapping, yapping, and snarling kikery he portrays in his work comes closest to the genuine Jews known to those of us who have had close contact with them.

Even this brief overview raises the question: How could such an unpromising gang have risen to the top of the literary heap?

Norman Podhoretz provides us with a clue: “Authority in writing,” he says, keynoting the work of all his co-racialists, “need not be accompanied by consummate skill or any other virtue of craft or mind, for like the personal self-confidence of which it is the literary reflection, it is a quality in its own irreducible right, and one that always elicits an immediate response — just as a certain diffidence of tone and hesitancy of manner account for the puzzling failure of many otherwise superior writers to attract the attention they merit.”23 By this Podhoretz seems to be saying that it is not sheer ability but brazen self-promotion — a Jewish specialty — that is the principal ingredient for literary success.

At times Saul Bellow behaves in a way characteristic of those Jewish writers who wish to convince us — a la Shylock — that they, too, are sensitive human beings. As they represent themselves, it pains them to be outside the dominant culture, but in reality they are just like everyone else — only, of course, having suffered and stewed in fate-laden historical juices for so long they are considerably more sensitive and aware than the frolicsome goyim they must live amongst. Bellow’s alter ego, Herzog, in remembering his boyhood, feels the stings even in the books he reads: “But I was poring over Spengler now, struggling and drowning in the oceanic visions of that sinister kraut…. I learned that I, a Jew, was a born Magian and that we Magians had already had our great age, forever past. No matter how hard I tried, I would never grasp the Christian and Faustian world idea, forever alien to me….”24

Although some Gentile authors have written on this theme of the Jewish outsider, it doesn’t really count unless we get it from the source itself — and in spades: now it’s the Shylocks who ventriloquize us; now it is we who have become a mere voiceless fellaheen to be strategically set up in fiction — and not only in fiction — for the purpose of reflecting the brilliance and sensitivity of Jewish wordsmiths.

The importance of Yiddish to Bellow’s style has been noted often. One Jewish reviewer speaks of Bellow’s style, in measured admiration, as “a continuous learned truculence” with a “voice box” that is rooted in Yiddish.25 And Richard Kostelanetz, chuckling at a fawning Gentile critic who suggested that Bellow’s “intellectually rich style” was due to its Yiddish origins, replies that “… Yiddish is decidedly anti-philosophic, full of words designed to cope with the dirt (dreck) of existence.”26

|

| Herman Wouk, Norman Mailer, Philip Roth |

One warmly-praised work of Bernard Malamud was The Fixer, a fictionalized version of the suffering of a Jew in Czarist Russia who was accused — falsely, we are told — of the ritual murder of a Russian boy. Most of Malamud’s fiction centers around this theme that Jews are the suffering race par excellence, placed on this earthball to endure pain, agony, and sudden and undeserved death: characters in a migrant morality play for the edification of those barbarian folk among whom the Jews are obliged to live.

When Jews write about non-Jews one has a sense that they brandish their skill with words as a weapon to score points — often relentlessly — against the alien world that oppresses them with its non-Jewishness. There is little sign that the Jewish writers care about their non-Jewish characters, except in a negative, manipulative way. Feelings of hatred or inadequacy on the part of Jews when facing the Western world are easy to understand, and a novel by a Jewish writer about the tribulations of Jewish life in the (to him) alien West could be of some interest (although not when each such work is heralded, ad nauseam, as a “great American novel,” and not when endless variations on the same theme are ground out from the New York publishing houses like loaves of unleavened bread). However, Malamud cannot even write genuinely about Jews without injecting sizable gobs of inflated and bogus “significance.” “As with some of Saul Bellow’s heroes,” writes Joseph Featherstone in The Atlantic, “you sense [in Malamud] a pumping, wheezing attempt to inflate the status of a character.”28

On Jewish prose in general James Yaffe, a Jew, says: “Its besetting fault is pretentiousness. It is characterized by long words, involved sentences, a pervasive heaviness of tone.” On Malamud in particular he comments: “In Jews and Americans Irving Malin praises Bernard Malamud for manipulating his characters into a final symbolic image.’… It takes a Jewish intellectual to imagine that successful characters of fiction are ‘manipulated.’ “29

Because of his obvious stylistic deficiencies Herman Wouk is not considered a “serious” writer by some critics. Yet his marathon novels regularly rise to top the lists; possibly they constitute a boon to suffering insomniacs with a penchant for best sellers. Wouk is best known for his war novels (The Caine Mutiny, The Winds of War, War and Remembrance), which are a sort of unofficial Jewish salute to those homely, commonsense, down- to-earth English and American Anglo-Saxons who never tire of pulling Jewish chestnuts out of the fire. Obligatory and heartrending scenes of Jews being abused in concentration camps and dying in “gas ovens” are a hallmark of his work.

One of Wouk’s regular-guy Americans, who finds himself only when he is lucky enough to meet and marry a Jewish girl from New York, explains why America must go to war against Germany: “Well, that’s why I’ve been reading this book [Mein Kampf], to try to figure them out. It’s their leader’s book. Now, it turns out this is the writing of an absolute nut. The Jews are secretly running the world, he says. That’s his whole message. They’re the capitalists, but they’re the Bolsheviks too, and they’re conspiring to destroy the German people, who by rights should really be running the world. Well, he’s going to become dictator, see, wipe out the Jews, crush France, and carve off half of Bolshevist Russia for more German living space. Have I got it right so far?”30

The Jews and the wartime Americans portrayed in Wouk’s books are often mildly flawed, but always wonderfully and warmly human; all the Germans are either monstrous, malevolent, or cowardly. Have we got it right so far, Mr. Wouk?

There are Jewish intellectuals who get jittery over any obvious concentration of Jewish power — political, social, or cultural. In the last case some have tried to deflect any reactive hostility by claiming that the Jewish putsch in literature was a temporary fad of the 1960s (it’s still going strong today). Alternatively, they deny that the work of American-Jewish writers has anything to do with their Jewishness. While even the likes of Bellow and Malamud are sometimes included in this disclaimer, it is Norman Mailer who is most often singled out as the Jewish writer who left his Jewishness in a Brooklyn alley. “Mailer’s consciousness of himself as a Jew is, I would say, quite unimportant to him as a writer, if not wholly negative,”31 stated the late Philip Rahv, a Jewish intellectual from New York who was one of the principal shapers of modern America’s literary tastes.

Mailer vigorously promotes the image of himself as a giant of American literature unaffected by the mind-set, thought patterns, and life-styles of his biological antecedents. Yet he worries about it. Speaking of himself in the third person he writes of his “fatal taint, a last remaining speck of the one personality he found absolutely insupportable — the nice Jewish boy from Brooklyn.”32

Theodore L. Gross, a Jewish professor of literature at Pennsylvania State University, doesn’t find Mailer’s Jewishness either unimportant or particularly insupportable: “The very fact that Mailer should isolate his Jewishness dramatizes the difficulties he had — unlike Emerson, Twain, Howells, Eliot, or Hemingway in previous generations — of being the representative writer of our time… Some of Mailer’s best work…is expressive, at least in part, of his Jewishness; it could be written by no author other than one who stood a little outside, and even felt intimidated by, the Protestant tradition in our literature which ended with World War II.”33

Another Jewish professor, Helen A. Weinberg, states it plainly: “…[T]here are in his work three motifs that seem to grow, either directly or perversely, out of his personal life as a Jew and his consciousness of himself as a Jew in history: they are his repeated references to the Nazis and their concentration camps as the central evil from which other, more recent evils — in politics, gangsterism, war, and technology — inevitably receive their sinister resonance; his almost aesthetic interest in watching and categorizing Gentiles…and finally, his attempt to create what Leslie Fiedler has called ‘super Gentiles’ as fictive characters with whom he may identify…”34 Weinberg also writes that Mailer’s activism is “uniquely Jewish” and that his characters reveal “the Jewish messianic sense.”

In his work Mailer roves the American landscape, sniffing at the strange, alien souls of its inhabitants, explaining to us the idolatrous nature of our obsession with movie stars and spectacular crimes, and analyzing our effort to conquer space — the latter a shame and a horror to the Semitic mentality. In one of his latest opuses Mailer takes his readers on an erotic and scatological tour of dynastic Egypt, that old enemy of the Jews, with its strange and hostile gods.

Mailer sometimes takes on the protective coloration of an “Irish” persona, but this in no way — not for a moment — obliterates his “fatal taint.” That vile blemish erupts again and again in his work: in his novels, from the portrayal of the Jewish soldiers in The Naked and the Dead to his scoring of long-dead adversaries in Ancient Evenings; in his essay “The White Negro”; in his short story “The Marshal and the Nazi”; and perhaps above all in his statement to an interviewer that he was “going to hit the longest ball ever hit in American letters.” In these eleven words, in their content and their delivery, in the jarring inappropriateness of the metaphor, one can hear clearly the aggressive nasality of the New York immigrants crowding the Lower East Side, the old-clothes peddler with his pushcart, the garment-center huckster. Everything Mailer writes or says reveals the spiritual makeup of the Brooklyn Jew. The scent of hate-encrusted millennia is exuded in every word he puts to paper.

“From his earliest days,” writes James Yaffe, “the Jewish child is bombarded with talk. He grows up in a family in which there is continuous conversation, constant weighing of the pros and cons of every major and minor point.” To the Jew, words are both weapons and a means of disguise, of camouflage. They serve to flatter, to cajole, to dissemble, or to demolish, as the occasion demands. In this respect there is no real difference between the Jewish novelist on one hand and his brother, the attorney and the huckster; all bring their professions into disrepute by employing words to manipulate rather than discover.

Jews are a wordy people, verbal to an extreme. They take great delight in the clever use of language. Talmudic scholars honed this skill through countless, grieving eons in the Diaspora, and shtetl rabbis lovingly added their own consummate touch. A convoluted reasoning with its own peculiar vocabulary that says one thing but means another, or nothing at all, became part of the genetic birthright of every Jew. Theological — and ultimately secular — hairsplitting and a non-Western juggling with the symbolic representations of reality bred their way into the Jewish national character. In the last few centuries, as never before, this acrobatic skill with words and symbols became a potent weapon in that most urgent of all Jewish imperatives: to survive. And not just to survive, but to prosper, to wax fat at the expense of the host nations who gaped at these acts of verbal and literary legerdemain with open-mouthed wonderment, like children at a circus, while their pockets were being deftly picked.

Philip Roth is no worse than most of the Jewish novelists who use language in this fashion, but he is singular in that the middle-class Jews whom he parades across the pages of his short stories and books are not caricatures, but realistic and credible renderings of some of the less lovely exemplars of his people. Roth rubs the noses of his Gentile readers into the foulness; he lances the boil of his Jewish psyche and asks us to recognize the eructations of his Semitic maladies as the brilliant effusions of a first-rank artist.

Roth drew much public attention to himself with the publication in 1967 of Portnoy’s Complaint. The treatment of the American Gentile at the hands of the Jew in this novel was evidence unmistakable even to the simplest mind that Jewish power in America — in this instance demonstrated by means of a popular novel — was now virtually absolute. The vilest insults could be spat out at the nation’s founding race, not only without a whisper of protest, but with deracinated Gentile readers gobbling it up with masochistic glee.

Roth’s hero lusts after the shikses, the Gentile females, particularly those from the old families with lineages traceable to the Mayflower. Sex is not the prime motive; rather the hero is actuated by resentment against what he perceives to be the cool insularity and quiet capability of the American-Anglo upper class — so far removed from the grubbiness and dirt of the shtetl.

One of the girls in the book is descended from an old New England family, a fact of great importance to Portnoy. who like Roth, was a Jew from Newark, New Jersey. “Imagine what it meant to me to know that generations of Maulsbys were buried in the graveyard at Newbury- port, Massachusetts, and generations of Abbotts in Salem.

Land where my fathers died, land of the Pilgrims’ pride… Exactly. Oh, and more. Here was a girl whose mother’s flesh crawled at the sound of the words ‘Eleanor Roosevelt.’ Who herself had been dandled on the knee of Wendell Willkie at Hobe Sound, Florida, in 1942 (while my father was saying prayers for FDR on the High Holidays, and my mother blessing him over the Friday night candles). The Senator from Connecticut had been a roommate of her Daddy’s at Harvard, and her brother, ‘Paunch,’ a graduate of Yale, held a seat on the New York stock exchange and (how lucky could I be?) played polo (yes, games from on top a horse!) on Sunday afternoons someplace in Westchester County, as he had through college. She could have been a Lindabury, don’t you see? A daughter of my father’s boss! Here was a girl who knew how to sail a boat, knew how-to eat her dessert using two pieces of silverware…”35

Portnoy seduces this girl and then exerts great effort to get her to fellate him — again, not for the physical gratification, but to “conquer” America, a parable of the Jewish assumption of power in the United States. “What I’m saying, Doctor, is that I don’t seem to stick my dick up these girls, as much as I stick it up their backgrounds — as though through fucking I will discover America. Conquer America — maybe that’s more like it. Columbus, Captain Smith, Governor Winthrop, General Washington now Portnoy. … I am a child of the forties …. You name it, and if it was in praise of the Stars and Stripes, I know it word for word!… Well, we won, the enemy is dead in an alley back of the Wilhelmstrasse, and dead because I prayed him dead — and now I want what’s coming to me. My G.I. bill – real American ass! The cunt in country ’tis of thee! I pledge allegiance to the twat of the United States of America — and to the republic for which it stands: Davenport, Iowa! Dayton, Ohio! Schenectady, New York, and neighboring Troy! Fort Myers, Florida! New Canaan, Connecticut! Chicago, Illinois! Albert Lea, Minnesota! Portland, Maine! Moundsville, West Virginia! Sweet land of shiksa -tail, of thee I sing!”36

Portnoy/Roth lets the mask slip a number of times. The difference between the planetary systems of the Jewish and the Gentile psyches — as demonstrated in the simple use of language — is clearly shown in a scene where Portnoy visits the parents of another of his Gentile girl friends and is amazed to discover that the household employs words to communicate: “My God! The English language is a form of communication! Conversation isn’t just crossfire where you shoot and get shot at! Where you’ve got to duck for your life and aim to kill! Words aren’t only bombs and bullets — no, they’re little gifts, containing meanings!”

One could be grateful to Roth for the “exposé” of Jewish hatred and contempt in Portnoy’s Complaint and in some of his other work; unfortunately, the wide acceptance of this novel also exposed the total collapse of the standards of the old America. As surely as the British fell at Yorktown or Napoleon’s troops at Waterloo, in Portnoy’s Complaint America’s founding race, under the frontal assault of Semitic invaders, saw its total demoralization and defeat.

In its literature a people’s national character — its identity — is reflected and defined. We have seen how under the increasingly absolute sway of the Jewish literati — Bellow, Mailer, Roth, and their kinsmen — the American national identity has become more and more Jewish. By and large, Gentile critics have welcomed with a fawning obeisance this transformation. “There are no more representative American novels than [Saul Bellow’s] Augie March,” wrote Granville Hicks in Saturday Review, and Walter Allen has said that “a recognizably new note has come into American fiction, not the less American for being unmistakenly Jewish.”37

It is not, however, only our national identity that is being altered; our native tongue is also undergoing a change toward greater Jewishness. Irving Howe, a Jew, is one who knows something of this aspect of the Jewish cultural putsch. It was he who wrote: “…[W]ith American literature itself, we were uneasy. It spoke in terms that were strange and discordant. Its romanticism was of a kind we could not really find the key to…”38

Since the fundamental natures of the two very different peoples — Jews and Americans — could never be bridged, the Jews stopped looking for the key and simply broke down the door. The language itself was transmuted by the intruders, as Howe tells us in his estimate of the “American-Jewish style”:

“…[There was] a forced yoking of opposites: gutter vividness and university refinement, street energy and high cultural rhetoric.

“A strong infusion of Yiddish, not so much through the occasional use of a phrase or a word as through an importation of ironic twistings that transform the whole of a language, so to say, into a corkscrew of questions.

“A rapid, nervous, breathless tempo, like the hurry of a garment salesman trying to con a buyer or a highbrow lecturer trying to dazzle an audience.

“A deliberate loosening of syntax, as if to mock those niceties of correct English which Gore Vidal and other untainted Americans hold dear, so that in consequence there is much greater weight upon transitory patches of color than upon sentences in repose or paragraphs in composure.39

“A deliberate play with the phrasings of plebeian speech, but often of the kind that vibrates with cultural ambition, seeking to zoom into the regions of higher thought.

“In short, the linguistic tokens of writers who must hurry into articulateness if they are to be heard at all, indeed, who must scrape together a language.”40

The more common image fashioned of the Jewish-American novelist, however, is that he is a master builder, a genius. This pretension is broadcast to the reading public by the critics, the apostles of literary worth. In reality, each architect of this image is just another garrulous, fast-talking Jew, pulling rabbits from a hat amid a great deal of hot air, convincing the rootless consumers of his product that shadow is substance, and proving once more that the most effective tricks are also the most ancient.

Conclusion

The continuing Jewish control of American letters shows no signs of lessening; it will be with us as long as Jewish influence in all facets of American life and politics remains almighty. Lest the philo-Semites fret that the pioneer putschists who made their reputations in the ’50s and ’60s are getting long in tooth and may soon shuffle off the scene, assurance can be found in the veritable army of young writers of correct peoplehood that has already been “discovered” and is waiting in the wings. In fact, it seems a new Jewish genius is discovered on the average of once every other week.

There are still Gentile novelists who do get published and reviewed favorably, but their work is usually innocuous fluff, with a heavy- handed and self-conscious emphasis upon “style” for its own sake. These novelists strain after new (and what they must consider charming) ways to say old things. But true style, Nietzsche said, means giving content to one’s life; it means writing with blood. As there is no genuine content in the inner lives of these Gentile writers, no blood, all that is left are tedious neuroses and vague complaints. These writers would have us believe that their tiresome scribblings about their paltry concerns are literature, but the void in their lives reflects in their work, however devoutly they try to dress it up in a precious style.

The Jewish novelists will continue, by and large, to interpret our world for us (which they alternately view as a mad, meaningless sideshow or as a threatening spear aimed at their vitals), but not without a lingering resentment from parts of the hinterlands. This fact was acknowledged by Alfred Kazin in 1966, when he wrote: “Definitely, it was now the thing to be Jewish. But in Western universities and small towns many a traditional novelist and professor of English felt out of it, and asked, with varying degrees of self-control, if there was no longer a good novel to be written about the frontier, about Main Street, about the good that was in marriage? Was it possible, these critics wondered aloud, that American life had become so de-regionalized and lacking in local color that the big power units and the big cities had preempted the American scene, along with the supple Jewish intellectuals who were at home with them? Was it possible that Norman Mailer had become the representative American novelist?” Yes, he had, Kazin concluded, because in the “frothy, turbulent ‘mix’ of America in the ’60s, with its glut, its power drives, its confusion of values,” when “the old bourgeois certainties and humanist illusions have crumbled,” the Jewish writer arrives on a white horse to show us “the lunacy and hollowness of so many present symbols of authority.”41

The sense of frustration on the part of the Gentile traditionalists, and Kazin’s gloating over it, are real, but the fact that many of the old literary themes have lost much of their relevance in a drastically changed world is not among the reasons for the demise of American letters. In the crumbling of the old values there are many new frontiers and new themes for a talented Gentile author: the dispossession of the Whites from the land built by their fathers; the ceaselessly marching feet of swelling, dark minorities that unchecked will one day soon be majorities; the splitting asunder of a nation now well beyond any sort of conventional redemption; and the rumbling, widening gap of hostility between what remains of the original American psyche and the “present symbols of authority,” in letters and elsewhere. This soul- testing, unlike any which Western man has experienced before, offers a rich lode for an able White writer.

Yet we will wait a long, long time before we see a novel dealing with these topics (from a White perspective) on the best-seller charts. An obvious reason is that however brilliant such a novel may be, it will not be touched by any major publisher, and by very few minor ones. No agent will handle it, no magazine or newspaper with any circulation to speak of is likely to review it, and few if any bookstores will stock it. There will be no talk shows for the author, no movie rights, nothing; nothing, that is, except the satisfaction and joy of writing of things that matter.

But there is another — related, but perhaps less obvious — reason: The prerequisite for the creation of great art of any kind (by our race) is the presence of a heroic spirit in the air; of heroic struggle; of a sense of the inherent nobility and the inevitable tragedy of the life of the individual; of a sense of joyous expectation for the future, despite this inevitable tragedy. The Jewish spirit is antithetical to all of this.

And so long as the Jews continue to exert a dominant influence on our lives — not only through the “literature” industry, but through all the other media of entertainment and edification on which they have fastened their grasp as well — the only spirit in the air will be that of the marketplace. Books will be written with the same motivation and judged by the same standards which apply to television dramas and Hollywood films today. Many of them will be well crafted and will provide entertaining diversion for their readers. But there will be no truly great literature written again until a new spirit, in tune with our own race-soul, has overcome the Jewish spirit and reshaped our way of looking at the world.

—

1 Hans F.K. Guenther, The Religious Attitudes of the Indo-Europeans (Clair Press, 1967), p. 108.

2 Louis Harap, The Image of the Jew in American Literature (The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1974), p. 110.

3 Ibid, pg. 121

4 Norman Podhoretz, Making It (Random House, 1967) pg. 48

5 Sol Liptzin, The Jew in American Literature (Block Publishing Co., 1966), pp. 1, 226.

6 Leslie Fiedler, Waiting for the End (Stein and Day, 1964), pp. 65, 67.

7 Sheldon Grebstein, in Contemporary America-Jewish Literature, Irving Malin, ed., (Indiana University Press, 1973) pp.176-177

8 Irving Malin, Jews and Americans, (Southern Illinois University Press, 1965) p. 7.

9 Fiedler, op. cit., 83

10 Robert Alter, “Sentimentalizing the Jews,” Commentary, September 1965

11 “The influence of the New York writers grew at the time New York itself, for better or worse, became the cultural center of the country… As polite, needling questions are asked about the cultural life of New York, a rise of sweat comes to one’s brow, for everyone knows what no one says: New York means Jews.” (Irving Howe, “The New York Intellectuals,” Commentary, October 1968.)

12 John Updike, the most widely acclaimed Gentile writer of “serious” fiction in the United States, has sensed which way the wind blows and made an effort at self-Judaization, issuing in the past decade or so several “Jewish” novels. “I created Henry Bech to show that I was really a Jewish writer also.” (World Progress, Winter 1982.) Although Updike, no doubt, speaks these words with his tongue in the cheek of a smirking face, they tell a tale of far greater significance than any story or novel he has written.

13 Allen Guttmann, The Jewish Writer in America (Oxford University Press, 1971), p. 225.

14 “At the moment that young Europeans everywhere . . . are becoming imaginary Americans, the American is becoming an imaginary Jew. . . . The Judaization of American culture goes on at levels far beneath the literary and the intellectual.” (Fiedler, op. cit., pp. 67,88.)

15 Podhoretz, op. cit., p. 161.

16 Ibid., pp. 310-311.

17 Ibid., pp. 309-310.

18 Richard Kostelanetz, “Militant Minorities,” Hudson Review, Autumn 1965. When the late Truman Capote said virtually the same thing on a nationally televised talk show, he raised something of an uproar. His career wasn’t damaged, however, perhaps because he — like Gore Vidal — belonged to that other powerful minority in contemporary American letters: the homosexuals.

19 Marguerite Pedersen, Censorship in the U.S. (Sovereign Press, 1978), p. 17.

20 “Literary Hustler,” Newsweek, March 1, 1976.

21 Robert Alter, After the Tradition (Dutton, 1969), p. 9.

22 Podhoretz, op. cit., p. 49.

23 Ibid., p. 153.

24 Saul Bellow, Herzog (Viking Press, 1961), pp. 233-234.

25 Judah Stampfer, “The Word Becomes a Voice,” The Nation, December 27, 1975.

26 Kostelanetz, op. cit. May-June 1985

27 Podhoretz, op. cit., p. 163.

28 Joseph Featherstone, “Bernard Malamud,” The Atlantic, March 1967.

29 James Yaffe, The American Jews (Random House, 1968), pp. 236-237.

30 Herman Wouk, The Winds of War (Little Brown, 1971), p. 217.

31 Philip Rahv, A Malamud Reader (Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 1967), p. xviii.

32 Norman Mailer, The Armies of the Night (New American Library, 1968), p. 134.

33 Theordore L. Gross, ed., The Literature of American Jews (The Free Press, 1969), p. 283.

34 Helen A. Weinberg, in Malin, ed., op. cit., p. 89.

35 Philip Roth, Portnoy’s Complaint (Random House, 1969), pp. 236.-237.

36 Ibid., pp. 235-236.

37 Walter Allen, The Modern Novel in Britain and the United States (E.P. Dutton, 1964), p. xxii.

38 Irving Howe, “Strangers,” The Yale Review, June 1977.

39 An editor or teacher can tell many war stories in this respect, of battles fought against the modern penchant for “loose syntax.”

40 Howe, op. cit.

41 Alfred Kazin, “The Jew as Modern Writer,” Commentary, April 1966.

Theodore Dreiser (1871-1945), author of Sister Carrie and An American Tragedy, was very far from being a master stylist or consistent social critic, but his courageous stand on the Jewish question stands in sharp contrast to the poltroonish antics of such present-day writers as John Updike. Predictably, very few of the Dreiser biographies speak of his position on the Jews.

Dreiser’s comments at a Symposium on the Jewish Question, which he convened in 1933 with the editorial staff of the American Spectator, are illustrative of his views: “Left to sheer liberalism as you interpret it, they [the Jews] could possess America by sheer numbers, their cohesion, and their race tastes…. The Jew insists that when he invades Italy or France or America or what you will, he becomes a native of that country — a full-blooded native of that country. You know yourself, if you know anything, that that is not true. He has been in Germany now for all of a thousand years, if not longer, and he is still a Jew. He has been in America all of two hundred years, and he has not faded into a pure American by any means, and he will not. As I said before, he maintains his religious dogmas and his racial sympathies, race characteristics, and race cohesion as against all the types of nationalities surrounding him whatsoever.”

Dreiser’s public comments caused his leftist friends — Jewish and Gentile — to put enormous pressure on him to recant. A threatening article by the Jewish novelist Michael Gold (“The Gun is Loaded, Dreiser!”) appeared in the Communist New Masses. However, the old naturalist stood firm. In a letter he wrote a few years after the public debate he stated: “I have not changed my viewpoint in regard to the Jewish programme in America. They do not blend as do the other elements in this country, but retain, as they retain in all countries, their race solidarity…”

Although H.L. Mencken and other prominent critics hailed Dreiser as a major American novelist, it is doubtful that were he alive today he could find a publisher for his work — due to his unwavering opposition to Jewish influence on American life.

Leave a Reply